Among the dead were two of the world's foremost climbing guides, Scott Fischer of Seattle and Rob Hall of New Zealand. Krakauer tourist climbers pay up to $65,000.)Īmong the people he was climbing with, six made the summit and four died.

(The magazine negotiated a lesser fee for Mr. Krakauer was on Everest as a paying client, assigned by Outside magazine to try to answer the question of whether the world's highest mountain has been devalued by the parade of trophy climbers looking for the ultimate thrill. Krakauer most appreciates being able to get up in the middle of the night, barefoot, and walk to the bathroom. In the few days that he has been home, Mr. He has a two-bedroom house that would hold barely hold half the people who shivered with him at the high camp on Everest. Krakauer said, at home in the Ballard section of Seattle, where the blue Olympic Mountains can be seen through low clouds. "Yeah, made the summit of Everest - for whatever that's worth," Mr. During a ferocious storm that kicked up around the summit on May 10, eight people died on the mountain - the worst single loss of life ever to occur on Everest. Krakauer or any other mountaineer would care to be associated with. The 1996 climbing season on Everest made history. What 42-year-old would not love to point to a picture of the 29,028-foot roof of the planet and utter the words that originated in mountaineering: been there, done that. Then there is the Everest summit, which he reached nearly two weeks ago.

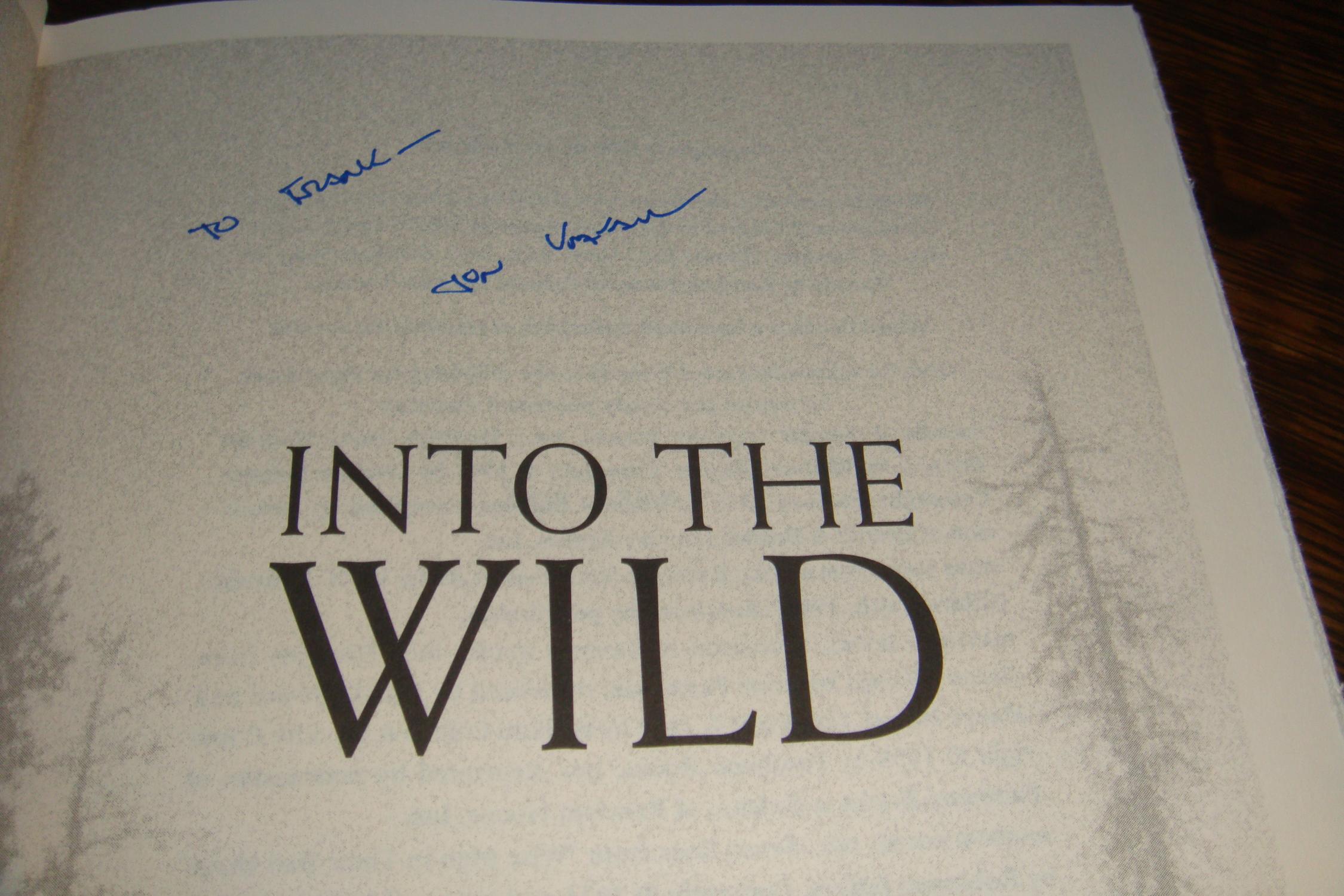

Krakauer, a longtime mountaineer, rich beyond a climbing bum's most vertical dreams. The book, "Into the Wild" (Villard Books), spent five weeks on the New York Times best-seller list earlier this year. About a year ago, he wrote a book about a highly romantic 24-year-old son of privilege who decided to chuck it all to live as a raw ascetic and ended up dead in an abandoned school bus near Mount McKinley in Alaska. What should be a season of triumph is shaping up as a long slog through second-guessing and doubt. All I know is I've never climbed a mountain with such a high ratio of misery to pleasure." "A few days ago, I just broke down and cried," he said, nursing a pot of tea. Krakauer has been having nightmares of late. Sorting through the psychic load may never end. This is the easy part, putting aside the physical scraps from climbing Mount Everest. At sea level in the verdant tangle of a Seattle spring, Jon Krakauer is sorting through things he brought back from the top of the world: summit rocks, pictures that will always haunt, the moon gear needed to walk at an elevation known as the Death Zone.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)